|

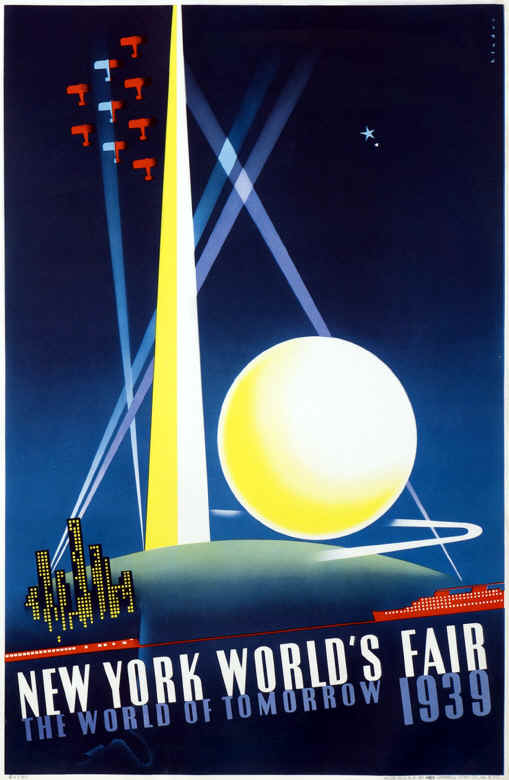

1939 NY World’s Fair Collectibles A time of innocence and Depression, summer dance bands and comic-strip adventures, baseball games and rumors of war in the evening news. It was 1939. And after ten long years of depression, the New York World’s Fair brought with it the glittering promise of the future. The Wonders of Oz were illusions--The 1939 World’s Fair was a wonder of science.

In May 1935, a Jackson Heights engineer, Joseph F. Shagden, and Edward F. Roosevelt, a distant relative of President Franklin Roosevelt, presented the idea of the Fair to a group of New York businessmen. A steering committee began meetings in June and by October a nonprofit corporation had been formed. The Flushing, Queens, location chosen for the Fair was the geographical and population center of the city but the activities of the Long Island Railroad, along with the indifference of local builders and politicians, had turned the marshy area into a monumental garbage dump, bounded on one side by the foul-smelling Flushing River. During the 1920s, the Brooklyn Ash Removal Company bought land to dump 50 million cubic yards of burned refuse which created one mound 90 feet tall—nicknamed "Mt. Corona"—by 1934.

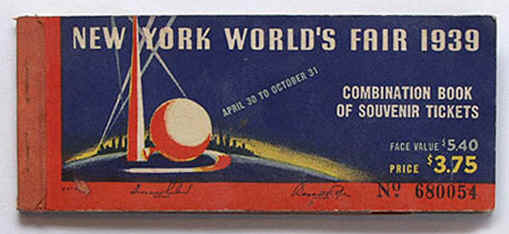

The Fair opened on April 30, 1939—the 150th anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration at Federal Hall in New York City. At 10:00 A.M. New York City Mayor LaGuardia cut the orange and blue ribbon at a dedication ceremony in the Temple of Religion. Trumpets heralded the procession of thousands of police officers and military men and public officials. And at 2:00 P.M. President Roosevelt dedicated the Fair. Altogether, 60 nations and international organizations took part in the Fair. Thirty-three states of the United States also had exhibits. With all of this cooperation, the Fair Corporation was able to achieve its main goal—to demonstrate the interdependence of all states and countries to each other in the world of the 20th-century world.

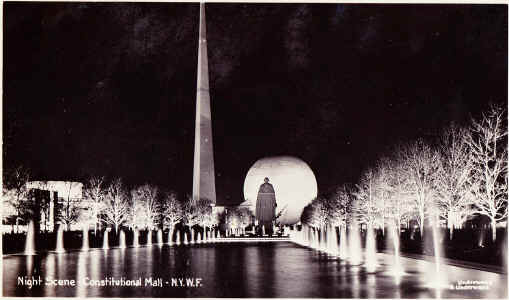

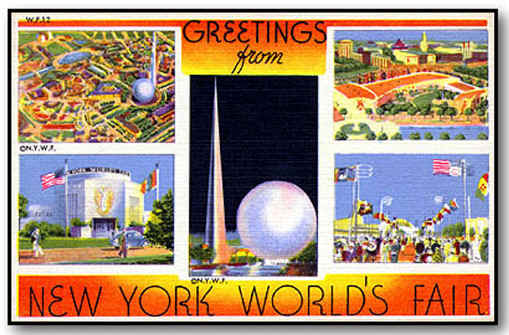

Photos of Mayor LaGuardia welcoming some dignitary or movie star to the World’s Fair filled newspapers. Visitors arrived by elevated and when they stepped out of the train, there was the Trylon and Perisphere, the abstract symbols of the World of Tomorrow. There they stood, white in the sun—white spire, white globe—as if in some sort of partnership.

Visitors walked down Rainbow Avenue, consulting their guidebooks. Some filled Constitution Mall, adorned with bright tulip gardens. Others rode in small trains of a dozen rubber-wheeled cars pulled by orange and blue electric powered tractors, and when the drivers blew their horns they played "The Sidewalks of New York"—"East side, west side, all around the town." Everywhere people walked in family groups and stopped to take photos in front of the exhibit buildings. Lady guides wore gray uniforms and hats. Anxious children and adults took their places in long lines that went up ramps alongside great streamlined buildings of rounded corners and windowless walls. Everyone wore their Sunday best. Here the cunning and ingenuity of builders and engineers reduced the world to tiny size. At the same time, things loomed up that were larger than they ought to have been, like the enormous walk-in eye of the Public Health Building. Here, too, resided an enormous man made of Plexiglas, with all his organs showing.

But the Fair’s main purpose was to showcase brand-name products, products which we take for granted today—Sealtest Ice Cream, Philadelphia Brand Cream Cheese, General Motors cars, Wonder Bread, Kodak cameras and film. Brand new and brand name foods made their debut at the Fair.

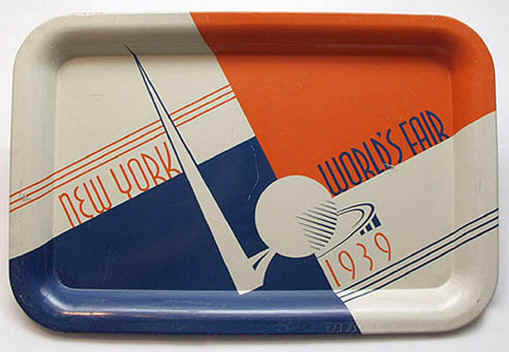

The Board of Design of the Fair, established in the spring of 1936, imbued with the principles of designers Bel Geddes, Loewy, Dreyfus and Teague, drew up rules and guidelines that helped make the exposition a success. Architects chose unusual shapes and materials for the Fair’s 375 structures, including 100 major exhibit buildings and 50 major amusement concessions. Though some were abstract, others were representational or emblematic, such as RCA's radio tube show and the twin prows of the Marine Transportation Building. The designers even regulated color in a rainbow-like way. The Trylon and Perisphere, the Fair's symbols, were dead white, the immediate surrounding area, off white. They conceived the main axis of the Fair in reds, the Avenue of the Patriots in yellows and golds, and the Avenue of the Pioneers in blues. They named the curved thoroughfare that connected the three ends Rainbow Avenue. World’s Fair Souvenirs

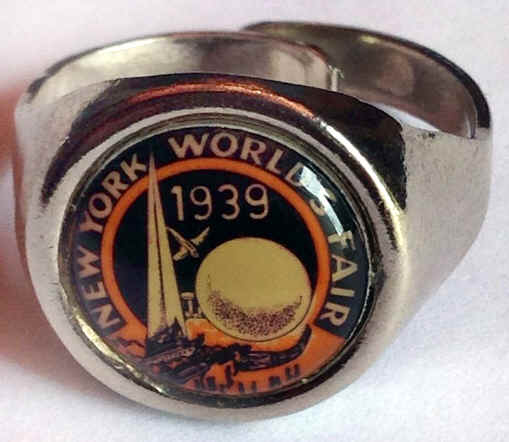

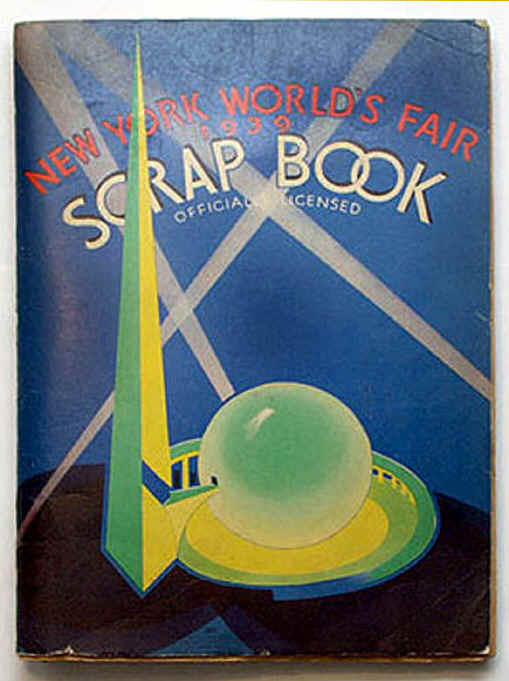

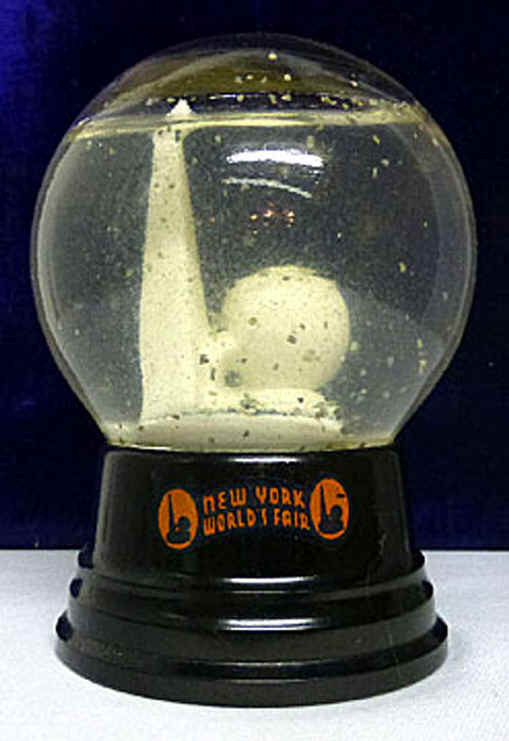

Kazoos had World’s Fair emblems emblazoned on them. Vendors sold a myriad of pins. Cloth banners and pendants sported images of the Trylon and Perisphere. The shear number of souvenirs from this two-year extravaganza numbered in the thousands. From a bizarre, but stylish, man’s smoking jacket made from silk interwoven with stylized Trylon and Perisphere symbols to movie viewers to jewelry to elegant dinnerware, the souvenirs taken home by visitors often ended up in some dusty attic. But today, they’re resurfacing, many in pristine condition.

As stated above, corporations gave away thousands of little advertising mementos so that visitors would remember them when they returned home. Lots of people had Heinz pickle pins. Planter’s also had their nut company’s Mr. Peanut, who wore a top hat and monocle. The Aviation exhibit gave out DC-3 charms. Scot Tissue gave away two of its new paper towels in an envelope. Of course, visitors could purchase such items as rayon material with the Dupont Pavilion woven into it, or a blown glass ship from the Glass Center, or streamlined Bakelite and metal cameras, designed by Walter Dorwin Teague, or Baby Brownie Cameras, also of Bakelite and metal and designed by Raymond Loewy, from the Eastman Kodak exhibit, or a rubber and glass tire ashtray from the B.F. Goodrich exhibit.

Brightly colored paper items with Art Deco and WPA influenced design, including matchboxes, posters, playing cards, bridge scorepads, and menus. Add to these items such things as ticket books, maps, postcards, photo packs, and sheet music.

Manufacturers used common materials—wood, plastic, metal and paper—to fashion souvenirs of the Fair. Coasters and tabletop radios of pressed wood, plastic salt and pepper shakers, metal, and paper posters. All designs had to be licensed by the World’s Fair Corporation. The Trylon was a skyscraping obelisk while the Perisphere was a great globe. Standing side by side at the Fair, together they represented the World of Tomorrow, the Fair’s theme. What’s interesting is how souvenir makers integrated both into the design of each souvenir. Their image appeared on jewelry, cosmetic cases, license plates, ashtrays, cigarette cases, toys and assorted games—every conceivable ornament and novelty. Illustrations (from top to bottom) As an avid collector of a variety of antiques and collectibles for the last 20 years, Bob Brooke knows what he’s writing about. Besides writing about antiques, Brooke has also sold at flea markets and worked in an antique shop, so he knows the business side too. His articles have appeared in many antiques and consumer publications, including British Heritage, Antique Week, Southeastern Antiquing and Collecting Magazine, www.OldandSold.com, and many others. To read more of his work, visit his main website at www.bobbrooke.com or his specialty antiques site at www.theantiquesalmanac.com |