|

The Origins of Glassmaking

When lightning struck sand, it creates

glass in the form fulgurites. Also known as ‘petrified lightning' or

‘lightning tubes', they form in sand and a wide variety of soils when

the moisture content is right.

The main component of regular glass is

silica, which melts at around 1650°C. Sand, generally is mostly made of

silica. The plasma generated by lightning strikes, on an average goes

well over 30,000°C.

Volcanoes

fusing rocks with sand creates obsidian glass. It is produced when

felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal

growth. Both of these natural events occurred many times before man

learned the techniques of glassmaking. Volcanoes

fusing rocks with sand creates obsidian glass. It is produced when

felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal

growth. Both of these natural events occurred many times before man

learned the techniques of glassmaking.

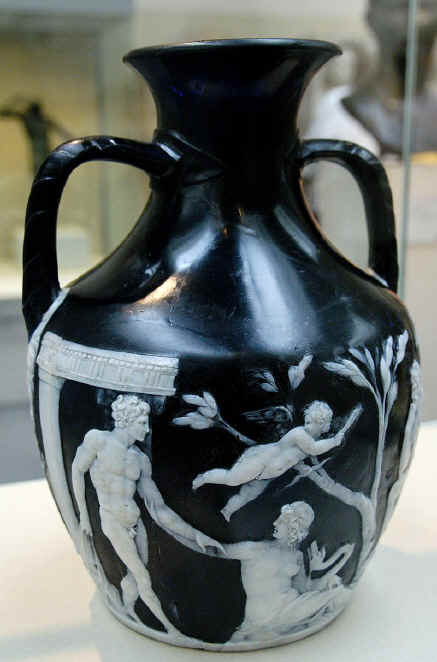

Where and when and man first learned

to make glass is not known, but cut glass has been traced back as far as

ancient Egypt, and engraved glass to ancient Rome. Glassmaking

flourished in all the countries under Roman rule. The celebrated

Portland vase was manufactured in Rome about 70 AD. It is the best known

piece of Roman cameo glass and has served as an inspiration to many

glass and porcelain makers from about the beginning of the 18th century

onwards. It has has been in the British Museum in since 1810.

The vase is about 25 centimeters high

and 56 in circumference. It is made of violet-blue glass, and surrounded

with a single continuous white glass cameo making two distinct scenes,

depicting seven human figures, plus a large snake, and two bearded and

horned heads below the handles, marking the break between the scenes.

Glassmaking gradually spread all over

Europe, and the trade was considered to be an art of high social

standing.

The methods and ingredients used to

make glass, and the tools used to form it, have probably changed less

over the years that any other process. The earliest glass was fused in

molds to make beads or formed around sand cores to make small vessels.

The event that changed glass making the most was the introduction of the

blowpipe. Historians don’t really know when this occurred either, but

generally, it was before the birth of Christ. Since then gravity,

temperature, and constant movement of the molten material have been used

in the formation of objects of glass.

In 1608 Captain John Smith brought

glassblowers to his new colony of Virginia. A glasshouse was built on

the mainland where plenty of fuel could be obtained. It is almost

certain that green glass bottles were made there. In 1621 another

glasshouse was built in Jamestown and glassblowers were instructed to

make beads for barter with the Indians. In 1632 in his report on the new

colony of Virginia, Captain Smith said that "glas" was sent

"home." There is little doubt that glassmaking was America's

first industry.

During the 18th century, English glass

of the Queen Anne period was imported into America in unbelievable

quantities. In 1712 Bristol glass was advertised in Boston, and in 1719

there was a shop there that exclusively sold glass.

The

first successful glass made commercially in America was that of Wistar,

a manufacturer of bottles, window glass, and other practical utensils

from 1739 to 1780, a remarkably long time for a colonial business. The

factory’s original product of brass buttons was so successful that the

plant expanded into the glassmaking field. The company was successful

enough to survive the depression years of the Revolution, and the

workmanship of the products made at Wistar’s two Southern New Jersey

plants (the other one was opened in Glassboro in 1781) became known as

South Jersey. South Jersey was usually free blown and tooled into simple

pictures, bowls and bottles. Later much of the South Jersey had

decorations of crimped and pinched bands of glass, trailing, and

quilting superimposed on it. Colors were usually those that were present

naturally, green, aquamarine and amber. The most original and inventive

technique attributed to the South Jersey workmen was the "lily

pad" motif. Blown out of the tag ends of the melting pots of green

window or bottle glass, this style was purely American and did not

pretend to imitate or compete with imported pieces. The

first successful glass made commercially in America was that of Wistar,

a manufacturer of bottles, window glass, and other practical utensils

from 1739 to 1780, a remarkably long time for a colonial business. The

factory’s original product of brass buttons was so successful that the

plant expanded into the glassmaking field. The company was successful

enough to survive the depression years of the Revolution, and the

workmanship of the products made at Wistar’s two Southern New Jersey

plants (the other one was opened in Glassboro in 1781) became known as

South Jersey. South Jersey was usually free blown and tooled into simple

pictures, bowls and bottles. Later much of the South Jersey had

decorations of crimped and pinched bands of glass, trailing, and

quilting superimposed on it. Colors were usually those that were present

naturally, green, aquamarine and amber. The most original and inventive

technique attributed to the South Jersey workmen was the "lily

pad" motif. Blown out of the tag ends of the melting pots of green

window or bottle glass, this style was purely American and did not

pretend to imitate or compete with imported pieces.

In the 1760’s, a man named Henry

Steigel began making glass in his father-in-law's ironworks. Steigel

decided to manufacture decanters and drinking glasses instead of

limiting the company to the manufacture of bottles and window glass. He

traveled to London and Bristol and studied the art of glassmaking and

hired workers trained in German, Venetian and English techniques.

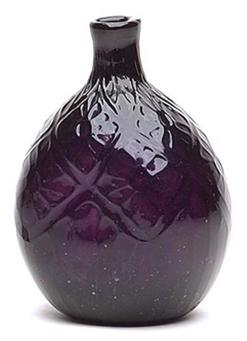

Advertisements from Pennsylvania to

Massachusetts and account books show that Steigel manufactured a wide

variety of tableware, including salt, creamers,, bowls, cruets, wine

glasses, tumblers, mugs, small containers, mustard, and smelling salts

and candlesticks. His colored glass was blown into part-sized molds to

give it a pattern, and then expanded to full size and finished, a

technique called pattern-molding. Steigel engraved and enameled his

flint glass. Flint glass is crystal made of pulverized flint.

Although

the origins of most of the patterns Steigel molded can be traced to

imitations of those used abroad, his daisy pattern is thought to have

been original. His daisies in a diamond or hexagon were mostly used on

pocket bottles. Steigel’s glass company was very successful, but when

the men of the Revolution began buying arms instead of glass, Steigel

lost everything, including his lavishly furnished mansion. Although

the origins of most of the patterns Steigel molded can be traced to

imitations of those used abroad, his daisy pattern is thought to have

been original. His daisies in a diamond or hexagon were mostly used on

pocket bottles. Steigel’s glass company was very successful, but when

the men of the Revolution began buying arms instead of glass, Steigel

lost everything, including his lavishly furnished mansion.

Another German, John Frederick Amelung,

founded the New Bremen Glass Manufactory near Frederick, Maryland in

1784. The company's clear glass decanters, glasses and goblets were

shallow wheel engraved, frequently bore commemorative inscriptions, and

set a high standard for the company's competitors.

The first glass factory west of the

Alleghenies was Albert Gallatin’s New Geneva Glassworks in western

Pennsylvania. In 1797 some of Amelung’s craftsmen migrated to Gallatin’s

Glasshouse near Pittsburgh. The availability of coal helped this area to

develop into a great manufacturing region.

After that, many important glasshouses

were founded in midwestern areas, including Zanesville, Ravenna, Mantua

and Kent, in Ohio.

Bakewell and Company of Pittsburgh was

established in 1808, and employed skilled English and Irish cutters. Its

cut and engraved glass rivaled the quality of imported glass. In

addition, Bakewell also manufactured free-blown and molded wares both

clear and in colors. Bakewell followed trends in both products and

patterns, and became one of the most diversified manufacturers of glass

in the century.

The early 18th century had many more

glass factories, and some of these, like the 1818 New England Glass

Company of East Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Boston and Sandwich

Glass Company of Cape Cod in 1825 became giants in the industry.

White Bakewell’s and the New England

Glass Company were producing glass in the best European traditions,

America took the lead in improvements in glass making techniques, like

mechanical pressing. Because of American inventions of the late 1820s,

glass could be pressed in a hand-operated mold into elaborately stippled

pieces, known today as "lacy glass." Simple molds manually

pressed together were made into salt cellars and cup plates,

inexpensively imitating cut glass.

The

second type of glass developed in America, was blown three-mold glass,

which also imitated the more expensive cut glass. In this process, the

blower expanded his gather of glass within a three-part mold, hinged to

a base, until it filled the pattern of the mold, some of which had cut

glass patterns incised on them. After the mold was opened, the piece was

manipulated with tools if further decoration was desired. Blown

three-mold pieces were produced in glass houses from New England to Ohio

in both clear and colored glass, and some in bottle glass. The

second type of glass developed in America, was blown three-mold glass,

which also imitated the more expensive cut glass. In this process, the

blower expanded his gather of glass within a three-part mold, hinged to

a base, until it filled the pattern of the mold, some of which had cut

glass patterns incised on them. After the mold was opened, the piece was

manipulated with tools if further decoration was desired. Blown

three-mold pieces were produced in glass houses from New England to Ohio

in both clear and colored glass, and some in bottle glass.

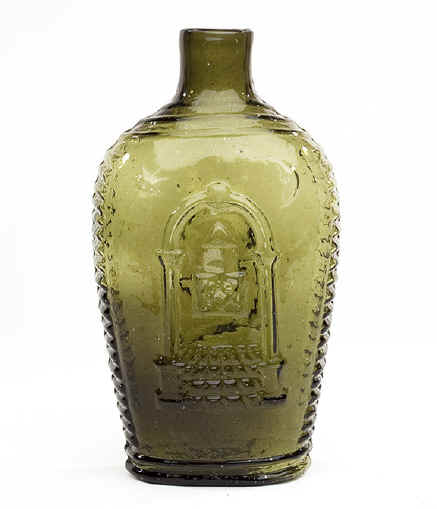

Among the most popular American

mold-blown objects was the historical flask, ornamented with political

figures, national heroes, and popular slogans. They were made throughout

the 19th century, and remain as a pictorial of history. The American

eagle appeared more frequently than any other motif; Masonic emblems and

political slogans were often used.

Shortly after the beginning of the

19th century, another technique developed around Pittsburgh,

pattern-molded glass. The shape and pattern of this ware was formed by

blowing the gather into part-sized dip, an open top, one piece mold, or

hinged molds. After it was removed from the mold, further blowing

expanded the glass into the desired size. The pattern, impressed by the

mold, spread out into a soft outline. Ribbed, swirled and diamond

patterns where the most popular designs. The "broken-rib" was

made by dipping the gather into the mold twice. After the gather was

blown into a rib mold, it was removed, given a twist, and blown into the

mold a second time. Then it was removed from the mold and expanded into

a flask or dish.

The earliest known examples of

American cut glass date from 1711 and they were of simple designs, like

stars in geometric designs. Engraving was also done in America. Fruit

and floral designs were the most popular, as were classical swags and

festoons. After the engraving, the pieces were hand-polished on wooden

wheels, thus giving them a soft luster distinct from the later

high-speed wheel polishing or acid bath. Fine cut designs were made by

Amelung Bakewell, the New England Glass Company, and the Boston &

Sandwich Glass Company.

By 1830, the American glass industry

had become so well established that it no longer had to depend on

foreign imports, and high tariffs were levied on glass from Europe. The

Baldwin Bill of 1830 that levied the tariffs, created a boom in American

glass manufacture so great that to historians, the Colonial Period of

American glass manufacture came to an end. It was now time for America's

glass industry to create its own style.

Illustrations from top to bottom:

A) "Glass Blower and Mold Boy. Grafton, W. Va." (Library of

Congress)

B) EXOGENIC FULGURITES, ELKO COUNTY, NEVADA Wedding scene, detail of the

side A of the Portland Vase

C) Masonic Historical Flask, Coventry Glass Works, Coventry,

Connecticut, 1824 – 1826

D) Attributed to Henry William Stiegel, Diamond Daisey Bottle, 1767-84.

Blown amethyst glass. Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery

|