|

Tariff Laws Cause Demand for American Made Glass

The new tariff laws placed on imported glass in 1830 decreased the amount of glassware on the market in America and fostered the development of the American Glass industry. By 1840, there were at least 81 glass houses in operation in the United States. Without the influence of the designs and patterns from other countries America was free to choose her own styles and preferences. In addition, growing prosperity created a demand for an enormous variety of glassware. In 1825 Deming Jarvis founded the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company at Cape Cod with the idea of pressing articles larger and more complex than salts. He foresaw a large market for cup plates of pressed glass. Early in the century, cups without handles were used for tea. In order to cool the tea, it was first poured into a saucer, and the cup then set on a small plate. Cup plates became very popular and about 1,000 different patterns have been cataloged. Conventional designs included early cut glass patterns like the heart series, naturalistic and geometric patterns. Historical patterns were also developed that featured prominent men and important events.

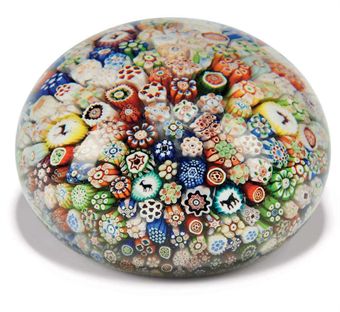

American manufacturers continued to manufacture lacy and pressed glass patterns in a wide variety of objects in many colors. The lead formula used for lacy ware gave the pieces intricate patterns brilliance and weight. The desire for new shapes and patterns increased, the glasshouses found it increasingly difficult to cater to changing fancies. Early pressed glass pieces were made of lead, a brilliant but expensive metal. In West Virginia a less expensive soda-lime glass was developed, and soon it was used by almost all of the glasshouses. The newer soda-lime glass did not have the ring or rich look of the traditional lead glass, but was suitable for the great variety demanded by the public. The cut glass market was even more threatened, because now cut glass which could only be made of lead glass had to compete with less expensive resources in addition to the less expensive pressing method. Cut glass manufacturers who did not add pressed glass items to their inventory began making cut glass items that could not be duplicated with pressing. The popularity of engraving both clear and colored glass reached its peak during this period of glassmaking history called The Middle Period, 1830 to 1880. Engraving was also used on glass of two colors, for example blue overlaid on white or one color flashed thinly on another. In addition, there was an acidic luster stain used to coat the glass which was then etched. Favorite etched patterns were fruit and florals, urns, hunting scenes and landscapes. Many of the designs of this period were so well done and elaborately detailed that they appeared to be sculpted in relief. The Middle Period also saw the

production of fine paperweights. The mosaic patterns, called millefiori,

were made from multi-colored rods of glass cut into pieces and arranged

in a pattern. The rods were fused together and then dipped in clear

glass repeatedly until the desired size was obtained. |

Jarvis

patented many improvements to the glass press, and by 1830 mass

production of pressed glass was becoming popular. Jarvis' plant

eventually produced sets of stemware and tableware, as well as,

candlesticks, vases, lamps, bowls and souvenirs.

Jarvis

patented many improvements to the glass press, and by 1830 mass

production of pressed glass was becoming popular. Jarvis' plant

eventually produced sets of stemware and tableware, as well as,

candlesticks, vases, lamps, bowls and souvenirs.